Go to Economics

Topics

Table of Contents

Introduction

- How the foreign exchange market is structured, who the major players are, and how they conduct their business.

- How exchange rates are quoted and calculated.

- The different exchange rate regimes throughout the world.

- The effect of exchange rates on international trade and capital flows.

- Capital restrictions imposed by governments

The Foreign Exchange Market and Exchange Rates

Introduction and the Foreign Exchange Market

The foreign exchange market (FX) is by far the world’s largest market. It has a daily turnover of about 10 to 15 times larger than global fixed income market, and about 50 times larger than global equities.

Exchange Rate

- It is the price or cost of one currency expressed in terms of another currency.

- It is the number of units of the price currency needed to buy/sell one unit of the base currency.

Consider an exchange rate quote of 1.4500 USD/EUR.

The numerator currency (USD) is called as the price currency and the denominator currency (EUR) is called as the base currency.

It implies that one EUR is exchangeable with 1.45 USD. Here, USD is the currency used to express price per one unit of euro.

- To determine appreciation or depreciation of a currency; if the quote rate increases in terms of the base currency → base currency has appreciated; and vice versa.

- If one currency in a currency exchange pair appreciates, the other currency depreciates.

Determine whether the following currencies have appreciated or depreciated.

- USD/EUR (1.416 → 1.4051)

- INR/USD (60.456 → 61.3869)

- CHF/USD (0.8895 → 0.8863)

- EUR depreciates relative to USD.

- USD appreciates relative to INR.

- USD depreciates relative to CHF.

Nominal exchange rate is the quoted currency exchange rate at any point in time.

Real exchange rate adjusts the nominal exchange rate for inflation in each country compared to a base period.

- Real exchange rate shows the relative purchasing power of currencies and has the following correlations:

- Directly related to nominal exchange rate.

- Directly related to price level in base currency.

- Inversely related to price level in price currency.

Market Participants

The forex market has a diverse range of participants. One way of classifying them is to group them based on buy-side and sell-side players.

Sell side:

- Large FX trading banks such as Deutsche bank, Citigroup, UBS, and HSBC.

- Other banks fall into the second and third tier of the FX market.

Buy side:

- Clients who use banks to undertake FX transactions.

- Corporate accounts: Corporations using forex transactions for cross-border trade of goods and services.

- Real money accounts: They usually have restricted use of leverage. Investment funds managed by mutual funds, ETFs, pension funds, endowments, etc.

- Leveraged accounts: Hedge funds, high-frequency algorithmic traders.

- Retail accounts: Individuals trading for their own accounts; tourists exchanging currency during international travel.

- Governments.

- Central banks: Intervene in the forex market to control their domestic exchange rate.

During 2012-13 the Reserve Bank of India sold billions of US dollars to strengthen the depreciating Indian rupee.

- Sovereign wealth funds: Countries with current account surpluses like Norway, UAE, Kuwait, and China direct international capital inflows into SWFs instead of holding them as foreign exchange reserves. SWF then invests these funds internationally in natural resources, infrastructure projects, and real estate to earn higher returns and exert more influence.

Market Composition

The largest turnover is in the swaps (49%) market, followed by the spot (33%) market.

Average daily FX flow between financial clients (51%) is higher than that between the sell-side banks (interbank market) (42%).

The top five currency pairs in terms of their % share of average daily global FX turnover.

- USD/EUR (23.1%)

- JPY/USD (17.8%)

- USD/GBP (9.3%)

- USD/AUD (5.2%)

- CAD/USD (4.3%)

Exchange Rate Quotations

Exchange rate is the price of one currency relative to another. Exchange rates are typically quoted at four decimal places. The ratio or exchange rate is quoted as price currency per unit of base currency.

Consider this quote: USD/EUR = 1.4000 or EUR/USD = 0.7142.

- Direct quote: A direct quote takes domestic currency as the price currency and the foreign currency as the base currency.

- Indirect quote: An indirect quote takes domestic currency as the base currency and the foreign currency as the price currency.

Direct and indirect quotes are the reciprocal of each other.

- Bid-ask: Currencies are always quoted as bid-ask. (This is from the perspective of a dealer, not from the client’s perspective).

- Bid rate is the rate at which the dealer will buy the base currency.

- Ask rate is the rate at which the dealer will sell the base currency.

A bid-ask quote of USD/EUR= 1.3990 – 1.4010 means that the dealer is willing to buy 1 euro for $1.399 and sell 1 euro for $1.4010.

The bid price is always lower than the sell price as the dealer makes money on the bid-ask spread.

Say the USD/EUR rate changed from 1.4 to 1.5. What is the appreciation/depreciation of each currency?

The base currency is EUR; the price currency is USD. The exchange rate goes up from 1.4 to 1.5. It means the base currency (EUR) has appreciated/strengthened. The USD has depreciated or weakened.

% appreciation of EUR =

% Depreciation of dollar =

Exchange Rate Regimes: Ideals and Historical Perspective

Every exchange rate is managed to some degree by central banks. The policy framework adopted by a central bank or the monetary authority to manage its currency relative to other currencies is called the exchange rate regime.

Why must the central bank intervene in the exchange rate?

This is because high exchange rate volatility can affect investment decisions or affect how foreign investors perceive the investment climate (risky or stable) of a country.

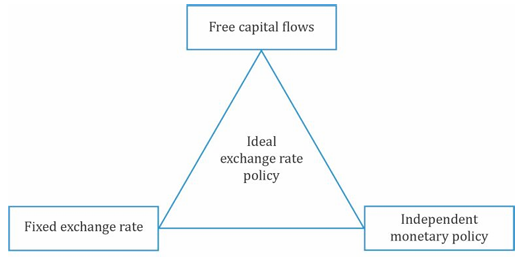

The Ideal Currency Regime

- The exchange rate between any two currencies would be credibly fixed.

- All currencies would be fully convertible (i.e., currencies could be freely exchanged for any purpose and in any amount).

- Each country would be able to undertake fully independent monetary policy in pursuit of domestic objectives, such as growth and inflation targets.

If 1 and 2 hold good, there would only be one currency and independent monetary policy will not be possible.

Historical Perspective on Currency Regimes

- Most of the 19th century, until the start of WWI in 1914: the US dollar and the UK pound sterling operated on the gold standard; meaning the price of each currency was fixed in terms of gold. Any other currency that fixed its price in terms of these two currencies was also indirectly operating on the gold standard.

- Trade imbalances, deflation, hyperinflation, and economies facing depression paved way for a new standard instead of gold.

- Towards the end of World War II in 1944 to the early 1970s: A Fixed parity system called “The Bretton Woods” system was introduced by John Keynes and Harry White; adopted by 44 countries replacing the gold standard. There were now fixed parities for exchange rate between currencies. There would be periodic realignments of currencies to bring them back to the fixed parity or equilibrium state.

- Inflation issues, countries not able to exercise monetary policy, and excessive capital mobility made countries move to the floating exchange rate system.

A Taxonomy of Currency Regimes

Exchange rate regimes for countries that do not have their own currency

- Formal dollarization

- Country uses the currency of another currency.

- The country cannot conduct its own monetary policy and imports the inflation of the country whose currency it uses.

- E.g., Panama uses the US dollar.

- Monetary union

- Several countries use a common currency.

- Countries do not have the ability to determine their own domestic monetary policy.

- E.g., the European Union.

Exchange rate regimes for countries that have their own currency

As we move down, the currency volatility increases and the ability to implement independent monetary policy increases.

- **Currency board system

- An explicit commitment to exchange domestic currency for a specified foreign currency at a fixed exchange rate.

- The country cannot conduct its own monetary policy and imports the inflation of the country whose currency it uses.

- E.g., Hong Kong issues HKD only when it is backed by equivalent USD holdings.

- Fixed parity

- A country pegs its currency within margins of ± 1% vs. another currency or basket of currencies.

- It is also called as conventional fixed peg arrangement.

- Exchange rate is maintained through:

- Direct intervention: Buying and selling foreign currency.

- Indirect intervention: Interest rate policies or regulating foreign transactions.

- E.g., Saudi Arabia uses a fixed parity with USD.

- Target zone

- Similar to a fixed parity, but with wider bands (± 2%).

- Authorities have more flexibility in monetary policies.

- Crawling peg

- Passive crawling peg allows for periodical adjustments in exchange rate, typically done to adjust for higher inflation versus the currency used in the peg.

- Active crawling peg is where series of adjustments are pre-announced and implemented over time making domestic inflation predictable.

- E.g. China.

- Crawling bands

- The width of bands used in fixed peg is increased over time to make the gradual transition from fixed parity to a floating rate.

- Managed float

- Monetary authority attempts to influence the exchange rate in response to specific indicators – balance of payments, inflation rates, or employment – without any specific target exchange rate.

- Independently float

- Exchange rate is entirely market-driven.

- Interventions are used only to reduce market fluctuations.

Exchange Rates and the Trade Balance: Introduction

If a country imports more goods and services than it exports, it has a trade deficit. This deficit must be financed by borrowing from foreigners or by selling assets to foreigners. Thus, a trade deficit must be exactly matched by an offsetting capital account surplus.

On the other hand, if a country exports more goods and services than it imports, it has a trade surplus. This surplus must be invested by lending to foreigners or by buying assets from foreigners. Thus, a trade surplus must be exactly matched by an offsetting capital account deficit.

The relationship between the trade balance and expenditure/saving decisions can be expressed as follows: $$(X – M) = (S − I) + (T − G)$$where:

- X is exports

- M is imports

- S is private savings

- I is investment in plant and equipment

- T is taxes net of transfers

- G is government expenditure

We can see from this relationship that a trade surplus (X > M) must be supported by a fiscal surplus (T > G), an excess of private saving over investment (S > I), or both.

In other words, a trade surplus indicates that the country saves more than enough to cover its investment (I) in plant and equipment. Excess savings are used to accrue financial claims against the rest of the world.

A trade deficit, on the other hand, indicates that the country does not save enough to fund its investment spending (I) and must reduce its net financial claims on the rest of the world.

Capital Restrictions

- Some governments restrict the inward and/or outward flow of capital.

- Restrictions on inflows might be due to strategic or defense-related reasons.

- During an economic crisis, capital might flow out of the country.

- Countries with scarce foreign exchange might restrict outflows and might also want to boost local investment.

- Over the long term, capital restrictions reduce welfare.